〉 Philemon

- Chapter

- Introduction

Philemon

Paul‘s Letter to Philemon

1. Title.

Inasmuch as this book is a personal letter, doubtless it originally bore no title. The earliest Greek manuscripts extant have the simple title Pros Philēmona (“To Philemon”), a superscription probably added by the unknown Christian who first brought Paul’s epistles together and published them as a collection.

2. Authorship.

This epistle specifically claims Paul as its author (v. 1). The fact that it deals only with a personal circumstance and that it reflects no attempt to promote any new teaching is a strong indication that it is genuine. Today scholars are virtually unanimous in accepting this brief epistle as authentically Pauline.

3. Historical Setting.

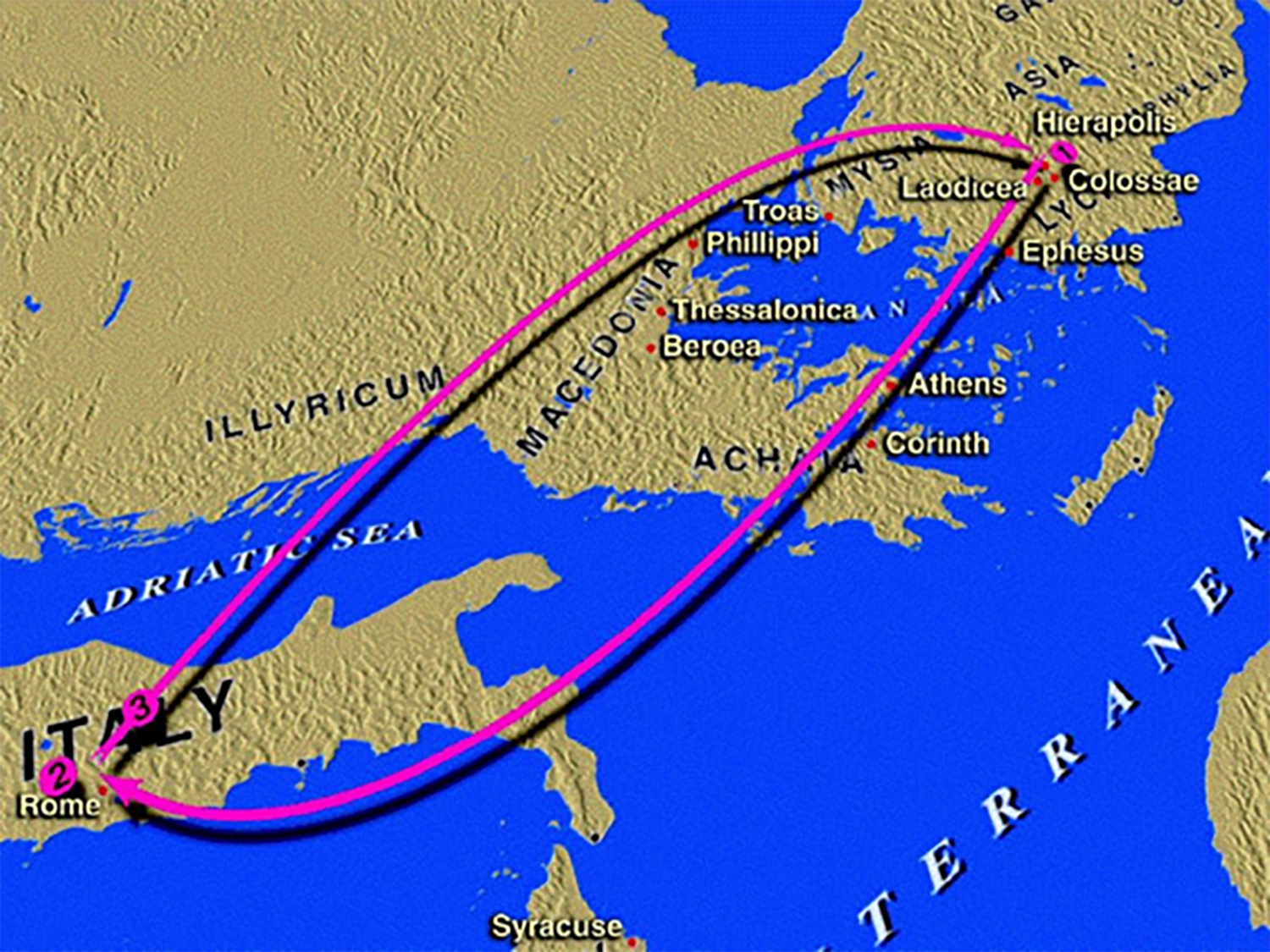

The Epistle to Philemon is a personal letter from the apostle Paul, while imprisoned at Rome, to a Christian named Philemon living in Colossae. For a discussion of the date of this epistle see Vol. VI, pp. 105, 106. It was dispatched at the same time as the Epistle to the Colossians, by Paul’s friend, Tychicus, and was occasioned by a crisis in the life of one of Paul’s converts. Onesimus, a slave of the Christian Philemon of Colossae, dissatisfied with his servile state, had run away, carrying with him some of his master’s money or possessions (v. 18; cf. AA 456). In time he found his way to Rome, as did many slaves, expecting to lose himself in the vast crowds of that city. While there Onesimus met Paul. Perhaps he was destitute and was prompted to seek out the Christians because of their charity, which he doubtless had often witnessed in his master’s household. Or, perhaps, while in Rome, he absorbed enough of Christian teaching to be suffering from a troubled conscience, and turned to Paul—who may previously have been a guest in Philemon’s home—for spiritual guidance.

Whatever his reason, Onesimus found a ready welcome and was inspired to minister devotedly to the aged apostle. His conscience and will prepared him to follow the path of duty, to redeem his past misdeeds by returning once more to his former master. Onesimus did not wait to see what response his master would make to Paul’s letter. Rather, he set out with Tychicus, Paul’s messenger. What his reception was no one knows, but it would be difficult to imagine that Philemon, as a follower of Christ, would not bend to so tender a plea of intercession. The dignified restraint of the letter reflects confidence on the apostle’s part that Philemon would receive Onesimus as a “brother beloved” (v. 16). We may suppose that Paul’s confidence was rewarded.

Without an understanding of the slave problem as it existed in the Roman Empire of Paul’s day the Epistle to Philemon cannot be fully appreciated. Slaves were a recognized part of the social structure and were considered members of their master’s household. Between the years 146 B.C. and A.D. 235 the proportion of slaves to freemen is said to have been three to one. Pliny says that in the time of Augustus a freedman by the name of Caecilius held 4,116 slaves (see Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1966 ed., vol. 20, pp. 776, 777, art. “Slavery”).

With so large a part of the population under bondage the ruling class felt obliged to enact severe laws to prevent escape or revolt. Originally, in Roman law the master possessed absolute power of life and death over his slaves. The slave could own no property. Everything he had belonged to his master, though at times he was allowed to accumulate chance earnings. Slaves could not legally marry, but were nevertheless encouraged to do so because their offspring increased the master’s wealth. The slave knew that he might be separated from his mate and children at the pleasure of his master. Slaves could not appeal to civil magistrates for justice, and there was no place where a fugitive slave could find asylum. He could never serve as a witness, except under torture, and he could not accuse his master of any crimes except high treason, adultery, incest, or the violation of sacred things. If a master was accused of a crime, he could offer his slave to be interrogated by torture in his place. The punishment for running away was often death, sometimes by crucifixion or by being thrown to voracious lampreys in a fishpond.

Some slaveowners were more considerate than others, and some slaves showed great devotion to their masters. Certain tasks committed to slaves were relatively pleasant, and a number required a high degree of intelligence. Often teachers, physicians, and even philosophers became slaves as a result of military conquest. Many slaves ran shops or factories or managed estates for their masters. But the institution of slavery was a school for cowardice, flattery, dishonesty, graft, immorality, and other vices, for above all else a slave had to cater to his master’s wishes, however evil. By about A.D. 200, conditions had improved greatly, and even more so after the spread of Christianitiy.

The Romans did not deny their slaves all hope of freedom. The law provided for their manumission, or liberation, in various ways. Most commonly, the master took his slave before an official, in whose presence he turned the slave around and pronounced the longed-for words liber esto, “Be free,” and struck him with a rod. Manumission could also be performed by various other means, such as writing a letter, making the slave guardian of one’s children, or placing on his head the pileus, or cap of liberty. But unless manumission was decreed by law rather than by a private owner, the slave was bound to remain a client to his master and to perform any obligations placed upon him at the time of manumission. In the Roman Empire it was possible for freedmen to rise steadily to positions of influence and even of civic authority, but their property, when they died without heirs, reverted to their former masters. One such instance was that of Felix, procurator of Judea (see Vol. V, p. 70).

4. Theme.

This little gem of Christian love and tact is unique in the canon of Scripture because it is a purely personal letter dealing with a domestic problem lem of the day—the relationship between a Christian master and a fugitive, but repentant, slave. It states no doctrine and offers no specific exhortation for the church as a whole. Nevertheless, that the Epistle to Philemon belongs in our Bible becomes amply clear through a study of the letter and its relationship to the other Pauline epistles. It is the only extant fragment of what must have been a considerable correspondence between Paul and individual members of his flock. It applies several basic principles of Christianity to daily life.

5. Outline.

I. Salutation, 1-3.

II. Commendation to Philemon, 4-7.

A. His Christian love and faithfulness cheered church members, 4-6.

B. Paul gratified by the spiritual achievements of his convert, 7.

III. Appeal for the Wholehearted Reception of Onesimus, 8-20.

A. The tactfulness of entreaty, 8-10.

B. The profitableness of Onesimus, 11-13.

C. Mutual respect between Paul and Philemon, 14.

D. The recognition of Providence, 15, 16.

E. The sufficient mediatorship of Paul, 17-19a.

F. The double debt of Philemon, 19b, 20.

IV. Conclusion and Benediction, 21-25.